Executive Summary

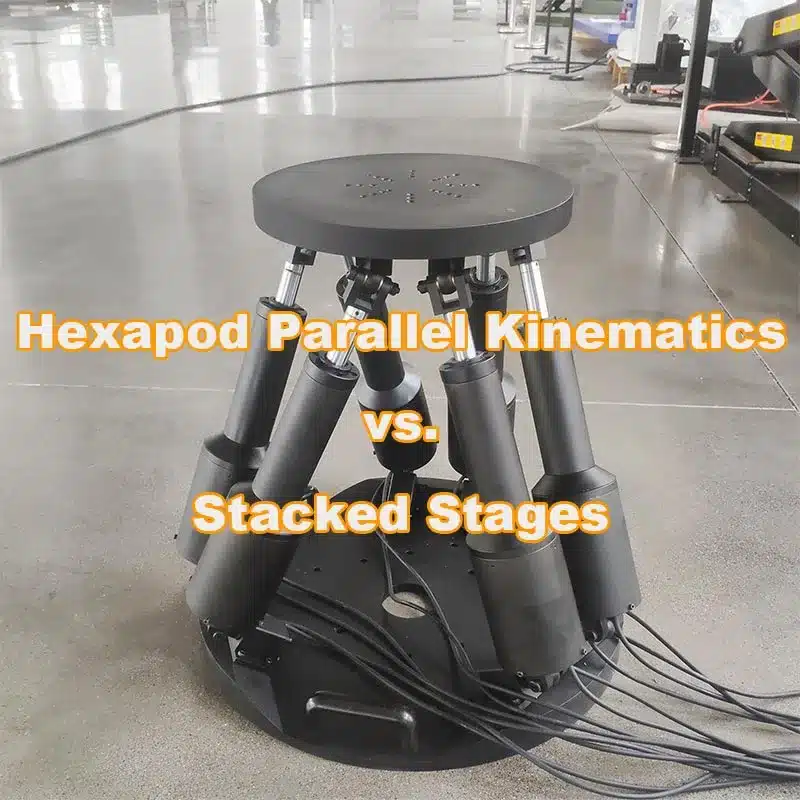

In high-precision engineering, a parallel kinematics hexapod(Stewart platform) is a 6-axis motion system where six actuators work in parallel to support and move a single platform, providing significantly higher stiffness, lower moving mass, and better path accuracy than serial stacked stages.

Unlike traditional serial mechanisms—where each axis is mounted on top of the previous one—the hexapod distributes the load across all six actuators simultaneously. This fundamental difference in architecture eliminates the “accumulative error” common in stacked systems, making parallel kinematics the gold standard for industrial applications requiring sub-micron precision, such as optical alignment, satellite testing, and advanced semiconductor manufacturing.

In contrast, a serial 6DOF (stacked stages) builds motion by stacking single-axis stages (or sub-stages) so each axis moves on top of the previous one. If you’re comparing them for precision automation, simulation, or test rigs, the “best” choice usually comes down to stiffness, dynamic behavior, workspace shape, payload inertia, and how you plan to calibrate the system.

Table of Contents

The Reality of Stacked Stages

In my years of designing motion systems at Allcontroller, I’ve seen many engineers default to “Stacked Stages” because they are intuitive. You take an X-stage, bolt a Y-stage on top, add a Z, and then try to cram three rotary stages on the very top.

However, we often encounter the “Cantilever Effect.” By the time you get to the 6th axis, the bottom axis (the X-stage) is carrying the dead weight of five other motors and cables. This creates a massive amount of inertia and structural deflection. If the bottom stage flexes by just 0.001 degrees, that error is magnified by the height of the stack—resulting in a significant “tip” at the tool point. In engineering, we call this Abbe Error, and in a serial stack, it is your worst enemy.

Quick definitions

Parallel kinematics hexapod: six legs/actuators simultaneously drive a moving platform; motion is computed through inverse kinematics (math mapping pose → leg lengths). Think “six people lifting and tilting a table together.”

Serial stacked stages: multiple axes stacked; each axis is mechanically and control-wise more direct (axis commands map closely to motion). Think “a drawer inside a drawer inside a drawer.”

Why Parallel Kinematics Hexapod Change the Game

When we switch to a parallel kinematics hexapod, we aren’t building a tower; we are building a “bridge.” All six actuators are connected directly from the base to the top platform.—Further reading: 6DOF motion platform applications

1. The Load-to-Weight Advantage

In a stacked system, the bottom motor might need to move 50kg just to reposition a 1kg sensor. In a hexapod, all six actuators contribute to moving that 1kg sensor. This results in a much higher Natural Frequency. In our testing, a hexapod can often maintain stability at frequencies where a stacked rig would start to resonate and vibrate like a tuning fork.

2. The "Virtual" Center of Rotation

This is where the magic happens for R&D. In a serial stack, your center of rotation (pivot point) is fixed by the physical location of your rotary stages. If you need to rotate around a point 100mm above your platform, you’re out of luck. With a hexapod, the pivot point is mathematically defined. We can program the “Software Pivot” to be anywhere in space—even outside the physical footprint of the machine. This is irreplaceable for lens alignment or laser processing.

Performance comparison: what changes in practice

Stiffness & structural behavior

Hexapod (parallel)

Typically higher stiffness-to-mass because loads are shared through multiple legs.

Less “lever arm” amplification compared with tall stacks.

Great when you care about micromotion under load, vibration sensitivity, or test repeatability.

Stacked stages (serial)

Stiffness often drops as the stack gets taller (each joint/guide adds compliance).

Cantilever effects and stage mounting matter a lot.

Can still be excellent if you engineer it carefully (short stack, high-grade stages, good mounting).

Rule of thumb: If your load is sensitive to tiny deflections or you need stable multi-axis orientation under force, hexapod often wins.

Dynamic performance (speed, acceleration, settling)

Rule of thumb: If your load is sensitive to tiny deflections or you need stable multi-axis orientation under force, hexapod often wins.

Hexapod

Can achieve strong dynamics because moving mass can be compact.

However, dynamics vary across the workspace; near limits you may see reduced performance.

Stacked stages

Dynamics often get worse as moving mass increases (each upper axis rides on all lower axes).

Settling can be longer due to structural modes in the stack.

What I usually watch: if your application is “move → settle → measure,” the settling time is the real KPI, not just max speed.

Accuracy, repeatability, and calibration reality

Hexapod

Achieving high absolute accuracy typically depends heavily on calibration (geometry identification, joint offsets, sensor mapping).

Repeatability can be excellent, but “truth in space” (metrology-grade accuracy) often requires a calibration workflow.

Stacked stages

Axis mapping is simpler (commanded travel ↔ encoder ↔ motion), so the calibration story is often more straightforward.

Still needs alignment and compensation, but the kinematics are less coupled.

Plain language: hexapod is more “math-driven,” stacked stages are more “mechanically intuitive.”

Workspace: shape and usability

Hexapod

Workspace is usually a complex 3D shape with coupled limits (translation and rotation trade against each other).

Great for “pose control” around a center, but less ideal if you need long stroke on one axis.

Stacked stages

Workspace is easier to visualize (sum of axis travels).

Easier to get long travel in X/Y/Z by selecting longer stages.

Payload, inertia, and center-of-gravity sensitivity

Hexapod

Loves compact payloads with controlled CoG.

Off-center or tall payloads can reduce usable workspace and increase actuator loads.

Stacked stages

Can tolerate certain payload geometries better, but inertia can punish dynamics and wear.

Practical tip: if your payload CoG may change (swappable fixtures), plan the mechanical interface and safety limits early—especially on hexapods.

Maintainability & integration

Hexapod

Fewer stacked mechanical interfaces, but more integrated system thinking (control, kinematics, safety).

Cable management is often cleaner.

Stacked stages

Modular; easier to replace a single axis.

But cable routing and accumulated alignment errors can become a long-term maintenance topic.

| Dimension | Parallel Kinematics Hexapod | Serial (Stacked Stages) |

|---|---|---|

| Stiffness-to-mass | Often strong | Depends on stack height & stage quality |

| Dynamics / settling | Strong but workspace-dependent | Often limited by moving mass & modes |

| Calibration complexity | Higher (kinematics + geometry) | Lower (axis-by-axis alignment) |

| Workspace shape | Coupled, non-rectangular | Easy to understand, rectangular-ish |

| Long travel axes | Less natural | More natural |

| Pose control (6DOF) | Native strength | Achievable but mechanically “tall” |

| Integration effort | System-level | Modular but can get mechanically complex |

When Should You Choose a parallel kinematics hexapod?

You need high stiffness and consistent pose control under load

Your process depends on short settling time and vibration resistance

The task is “precise 6DOF positioning around a working volume,” not long travel

You can support a calibration workflow (or want the vendor to deliver it)

Parallel kinematics hexapod Selection checklist

What is the payload mass + inertia + CoG range? (not just weight—rotation inertia matters)

What is the required settling time at target accuracy?

What is the usable workspace requirement (including combined rotation + translation)?

Environmental forces: vibration, process forces, cable forces, external tooling loads

Commissioning reality: who owns calibration, compensation, and acceptance testing?

FAQ: Parallel Kinematics & Hexapods

Is a hexapod more accurate than a serial stack?

Generally, yes. In a serial stack, errors in each axis (pitch, roll, yaw, and linearity) accumulate. In a hexapod, errors are “averaged” across the actuators, and there is no moving cable drag to introduce parasitic forces.

Can a hexapod handle heavy industrial payloads?

Absolutely. Because the load is shared by six struts in parallel, we have designed systems for Allcontroller clients that can position payloads over 2,000kg with micron-level repeatability.

Final Thought for Engineers

The shift from serial to parallel kinematics is like moving from a ladder to a tripod. One is easier to understand, but the other is fundamentally more stable. If your project is hitting a “precision ceiling” with stacked stages, the bottleneck likely isn’t your motors—it’s your architecture.

Would you like me to provide a kinematic simulation of how a 6DOF hexapod would perform under your specific payload and workspace requirements?